Louis Jarvers, MPA (Columbia University, New York / Hertie School, Berlin) & Julia Handle, MA (King’s College London)

Executive Summary

To better understand the connection between NFTs and far-right extremist content, we collected 7.5k NFT and their metadata from 11 blockchains. Categorizing the NFT by their title, description, details and visual assessment of the downloaded images/GIFs/videos, we conclude that far-right extremist content is spread via NFTs on different blockchains. Looking at the metadata and images of pre-selected 4.5k NFT from a keyword search, only a small share of NFTs is clearly extremist (2%). Much more content with relevant keywords in NFT metadata could be used for extremist purposes but is not extremist per se (approx. 15 %).

We learned that more specific keywords, produce more relevant results, that extremist slang/code is propagated into NFT descriptions and yields more extremist results when searched for. But: Extremist code only produces clearer results as long as the keywords remain distinguishable and not context-dependent. Context-sensitive, extremist “codes”, such as number combinations, cannot be detected with a keyword-based search method. This produces an unknown share of undetected extremist NFTs. The classification process was done manually which is a time-consuming process that does not scale well with more data. Automatization or even AI-based approaches to support the manual work are challenging since the categorization as extremist remains contextual and usually requires a description-image-context combination.

Overall, the analysis remains a spot-check since it is impossible to collect all NFTs across multiple chains; just like some NFTs remain unseen if relevant keywords are unknown. We conclude that, while NFT are not yet a major ground for extremists to play on, it is obvious that there is potential for exploitation of the decentralized web. As with many other technological developments, no one can say for sure what role web3 technologies will play in the future. To preempt the possible deterioration, we recommend to increase research on the exploitation of web3 in the field of national security studies and/or counter-terrorism. Here, data analytics on blockchains must go beyond financial interests: Security research around web3 should leverage the transparency of blockchains to quantify pending security questions, reduce the uncertainty of this technological development and anticipate future needs for law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Future “Internet intelligence” (INTINT) requires a close integration of classical open source intelligence (OSINT), social media intelligence (SOCMINT), and blockchain intelligence (BLOCKINT) to address the growing security concern around web3.

Introduction: Web3 Trends Raise Security Questions

Extremists, be it right-wing, left-wing or jihadists, make use of the Internet just like everybody else does – only with different intentions. From the mere presentation of information on static websites to active recruitment in closed, encrypted chatrooms and the spreading of propaganda, the Internet has served as an enabler for recruitment and radicalization. While researchers agree, that the Internet is rarely the sole driver of radicalization, it can for sure act as a facilitator.

When trying to prevent or counter extremists’ use of the Internet, organizations and projects frequently face the same issues: They are too late. Often, extremists are faster to move to new platforms, escaping efforts of de-platforming or a possible ban of accounts, quickly adapting to latest developments and trends. Governments, law enforcement, and civil society therefore strive to get ahead of current development in order to create tangible and impactful countermeasures. As the Internet as we know it is in a state of constant change, this proves to be a difficult task.

Advocates and critiques discuss the future of the current Internet under the term “web3”. Characterized as “decentralized online ecosystem based on blockchain”, web3 comprises distributed ledger technologies (and buzzwords) like crypto currencies, the metaverse, (non-fungible) tokens, or smart contracts. While the Facebook company “Meta” has already burned over $15 billion on its metaverse development, more and more private firms are rushing to invest into distributed ledger technology, and banks project astronomical values of web3 in 2030, the developments around web3 are raising questions around security and abuse: Cryptocurrencies are already notorious for funding terrorism and extremism – so what happens if NFTs with extremist content are now sold to fund white supremacists? What happens when the virtual reality avatars and metaverse spaces no longer only appeal to game nerds, but are used by terrorists as training camps or rooms to plot attacks? What happens when distributed file systems based on blockchain technology become (even) more prominent storage and exchange facilities to share bomb-making instructions or fascist propaganda? Or terror group set themselves up as "Decentralized Autonomous Organizations" with anonymized but automatized decision making processes? As welcome as the developments around blockchains, smart contracts, and NFTs are technologically, we must critically examine their role in propaganda, funding and facilitating terrorist and extremist contexts.

This paper aims to scrutinize security questions around Web3 with particular regards to extremism on non-fungible tokens (NFTs). Anticipating terrorist and extremists organizations to make use of NFTs and tokenization in general, the paper zeros in on the current spread of extremist content across different block chains. As research has focused on Islamist use of the Internet and lacks data for the far-right, the paper analyses the use of NFT by the far-right.[1] The paper first elaborates on the connection between terrorism, web3 and the future of Internet-related crime, before explaining the research approach undertaken for the data analysis on NFT metadata. After presenting the assessement on the current spread of extremist content on NFTs across 11 different blockchains, we assess the results in light of further research and discuss strategies to tackle extremism and crime related to NFTs.

In Context: Terrorism, Web3, and Future Internet Crime

Terrorism, Extremism & Internet

The emergence of the Internet has had an immense impact on the way extremist and terrorist organizations operate. It has changed the structure of extremist groups from rather hierarchical to a bottom-up, more open approach that allows for rapid growth and a more proactive participation. The velocity, replicability, and customizability of digital media, such as images, videos and animations (including memes) are combined with large online audiences, minimal barrier to publish and retrieve content as well as and largely anonymous interaction with the material and peers. This way, the Internet plays an outstanding role in disseminating far-right thoughts, especially when covered in borderline non-extremist concepts. While recruitment and radicalization certainly takes place on the Internet, it is also used for more logistical and practical things. Extremists use social media to inform about their activities and achievements, creating an image of growth and opportunity and reaching a large audience with minimal effort. They coordinate and organize their own activities as well as their finances through the Internet, making the need to be geologically close to each other obsolete.

Despite the constant evolvement of the use of the Internet, extremist motives have changed little. While debates around how to counter terrorists’ use of the Internet have offered many different solutions, one thing has become clear: the online and offline world can no longer be looked at separately. The two worlds have become so intertwined that they need to be understood as two co-dependent spheres, constantly influencing each other. As research on current trends is at risk of being overtaken by the rapid technical developments, researchers, practitioners, and law enforcement need to find a way to closely cooperate and identify possible technological trends that may rise in the near future – for example on web3.

As extremist and terrorist groups are on the constant lookout to innovate their ways of operating in order to create more impactful actions, Web3 is certainly on their radar. So far, literature on extremists’ use of Web3 remains scarce – only few publications and articles dive into the possible exploitation of the decentralized web by extremists. Therefore, the authors of this paper decided to take a closer look at developments in Web3, more specifically at NFT, to further elaborate on their possibly harmful exploitation.

For a long time, academic literature has extensively focused on the study of Islamist extremism online, despite almost all extremists using the Internet. This is likely due to IS propaganda being most prominent during the second decade of the 2000s, creating fear and concern for policy makers – resulting in more funding for research. This imbalance has changed in the recent years and this paper aims at contributing to this development by focusing on the far-right. Research has not yet focused on the exploitation of web3 by the far-right per se, but rather focused on specific platforms bases on the decentralized web, such as Bitchute. This paper will not take into account the whole sphere of Web3 either, but focus on the exploitation of NFT.

This paper follows Cas Mudde’s definition of the “far-right” that divides the far-right in two subgroups: the extreme right and the radical right. The former rejecting the essence of democracy itself and the letter accepting democracy but opposing fundamental elements of a liberal democracy such as minority rights or the rule of law.

Web3 and the Future of the Internet

While trying to fight online extremism, governments as well as civil society organizations often struggle to keep up with the

flexibility of extremist groups to adapt to latest (technological) developments, often due to structural restraints to act in an ad-hoc manner. This paper therefore sets out to analyze a possible

new space for extremists to exploit – the Web 3.0.

The concept of Web 3.0 (a term minted by Ethereum co-founder Gavin Wood) exists only with reference to the Web 1.0 and the Web 2.0. While the first generation of the Internet regarded users mostly as readers of content on static websites (“read-only”), the Web 2.0 establishes platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter or WordPress, where users create content themselves (“read-and-write”). After 15 years of experience with platform providers, their power and struggles to regulate them, the Web 3.0 seeks to decentralize the Internet. The decentralization comes with three inherent changes to the technical infrastructure of the Internet, namely “individual smart-contract capable blockchains, federated or centralized platforms capable of publishing verifiable states, and an interoperability platform to hyperconnect those state publishers to provide a unified and connected computing platform for Web 3.0 applications”. (Liu et al., 2022). The results is an Internet setup that provides users with the power to not only read and write content on the Internet but to also own it as shareholders of decentralized platforms. Blockchains are central building blocks to the web3 infrastructure as they serve as decentralized data storages that are transparent and fraud-resilient. Managed by peer-to-peer computer networks, blockchains usually store relevant information, such as cryptocurrencies, smart contracts, identity information or property rights (usually in the form of “tokens”). These property rights include so-called “non-fungible tokens” (NFT) who serve as unique digital identifiers and often represent ownership over digital objects, like images, videos or animations. Following the logic of transparent and fraud-resilient data storage on a blockchain, NFTs allow a user to own a digital object even if the digital reproduction methods easily copy images or videos. For the context of this analysis, we abstain from the discussion of the “uniqueness” of NFTs (let alone their usefulness) but simply acknowledge that NFTs are being minted (i.e., produced) and sold worldwide. We also acknowledge the integral nature of NFTs to the web3 development since other components, like decentralized platforms (e.g., metaverse) or decentralized file sharing solutions, can integrated NFTs as blockchain-based elements.

Future Internet Crimes

"We do not know what we do not know”

– INTERPOL Technology Forum on Web3

Inerasable photos and videos distributed across blockchains, terror financing via NFT trading, or highly immersive radicalization techniques via virtual reality? At this point it is unclear what importance will be attributed to web3 in the future, so law enforcement and security agencies are facing the immense task to assess the threat that might evolve from a more decentralized Internet. Interpol and Europol, as well as national law enforcement agencies, are working towards developing the capabilities to face the dangers of Web3. Threats and crimes on web3 can be separated into two groups: crimes that are already known and are adapted into the decentralized web, and previously unknown crimes that only the new (technological) characteristics of web3 enable. These new crime do not only seek a new digital niche but have not been seen before. Knowing of the abundance of potential threats, we focus on four relevant fields of crimes and the impact of web3 on their execution:

-

Terrorism & Organized Crime: More versatility of crypto currencies in a web3 world will boost the current uses of Monero, Zcash or DASH as a source of income through donations, drug trafficking or money

laundering. Web3 technology is also expected to enable extremist groups to target their propaganda more precisely at possible recruits. Moreover, new crimes and challenges will arise: As content regulation on existing social media platforms is already tough, identifying distributers and deleting content on web3 will

become nearly impossible. This makes Web3 a potential safe haven for the distribution of propaganda. As a new threat, web3 developments foster the integration of virtual reality in social platforms. Metaverses allow for the creation of

a virtual world that can serve as an immersive breeding ground for radicalization and recruitment. Not only can a virtual ‘Caliphate’ or white supremacist state can be created that operates

fully to the extremists’ beliefs and rules, but also training such as recreating certain scenarios or inspecting possible targets. The future web also creates potential new revenue streams: Selling extremist NFTs opens new market for extremist

memorabilia, tokenized certificates or digital “souvenirs” with buyers among, both, like-minded extremists and curious passer-bys.

-

Disinformation & Hate Speech: In the past couple of years, the dangers of mis- and disinformation became evident and demonstrated that information that is put out

on the Internet can lead to real life actions. As virtual reality-bound platforms, like the metaverse, seek to increase the level of psychological immersion into the virtual world, these web3

platforms might serve as a vehicle to gather a deep understanding of individuals’ interests and further use these insights to manipulate and create tailor-made content. This is particularly

hazardous if the infrastructure of platforms is decentral and lacks attributability and accountability. In addition to this new threat emerging from web3, we also expect disinformation and

hate speech to quickly shift to new platforms. It comes as no surprise that this paper found hate speech minted into numerous NFTs while analyzing metadata for extremist content. The

embedding of hate speech, harassment or disinformation in blockchains is further aggravated as deleting content on a chain is impossible. The combination of effects may cause a substantial

threat to the wellbeing of civil society and democracy.

-

Harmful Content & CSAM: Terrorist propaganda or disinformation is not the only form of harmful content that is to be found on the decentralized web. Other areas that are relevant

fields of action for law enforcement are emerging such as child pornography or sexual violence. These known crimes and hazards will likely use the emergence of web3 technologies as a new

field to develop onto. One example is the distribution of Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) that is easily accessible on centralized Internet technology (download servers, chat forums,

thread boards) and will likely spread onto NFTs, metaverse spaces or smart contracts. Here, the problems around attributing and deleting harmful content aggravate once CSAM is minted into an NFT. The new technology also renders certain existing defense

strategies of law enforcement useless. Going on step further, immersive metaverse platforms might as well provide the cyber-space for sexual

harassment themselves, as reports show. Crimes, such as in the involuntary exposure to psychologically harmful

content, become more relevant as users are deeply immersed into a platform and cannot “look away”. With these questions, not only content moderation (as with web2) but also action moderation

will drive imperative security question in web3.

- Money Laundering & Scams: As the decentralized web offers new opportunities to disguise one’s own identity, it offers a space for a variety of financial crimes including money laundering and all sorts of scams. The trading of NFTs, for example, offers an opportunity to enter illegal money into the legitimate economic cycle. One simply has to create an NFT, using illegal money, sell it, and then declare the profit as legit money. While NFT in theory is proof of ownership in itself, there are also numerous ways to use them as a scam, e.g. by selling one NFT multiple times on different blockchains. OpenSea has stated itself that a sample trial has exposed 80% of NFT on its marketplace to be illegitimate or plagiarized. Both types of crimes are known but will exploit the digital niche that web3 opened.

Potentiating the threat of the individual crimes fields mentioned above, web3 technologies are largely interconnected. Crypto-currencies are used to buy land in a metaverse; smart-contracts regulate entry permissions to a metaverse parcel; NFTs are displayed and sold in a metaverse space as digital property. The interconnectedness drives big hopes for the success of web 3, while amplifying the relevance of individual web3 elements. Crypto-currencies like Bitcoin, for example, were not treated as a real payment method in the beginning. Nowadays you can shop furniture, sports equipment, web services, smartphones, jewelry, games, or insurances with it. In Switzerland, there are over 150 ATMs to withdraw Swiss Franc from your Bitcoin account, as well as a local tax authority that accepts bitcoins to settle tax debt. And this trend is unlikely to break, since DLT-based technologies like decentralized finance, metaverse platforms and NFTs are native to crypto payments. NFTs, as another example, are still widely criticized as “useless” digital objects that only serve as much purpose as any other digital picture or video saved on a machine. While one can argue about the value of digital copies on a computer, their importance rises drastically if they are seen corresponding with other technological advancements, for example, when being display in metaverse property, treated as certificates of attendance or proof of property. More accessibility and more frequent use of one web3 technology simultaneously enhance the importance of other web3 technologies. This way, the triumph of crypto-currencies and/or the metaverse might make NFTs the digital items of the future.

From a security standpoint, the question of mass adoption of web3 technology is important but not decisive. If NFTs are widely used, the question of extremism or abusive content on NFTs becomes more relevant; but even if NFTs remain a niche, that potential danger of their abuse must worry law enforcement agencies and require a legal response: NFTs with extremist content can still be abused to propagandize extremist ideology. The decentralized creation and ownership of NFTs make it particularly hard to delete radical content; the easy adoption and handling of NFTs make it a low barrier medium for pictures, videos, texts, audio and other formats of extremist content. In combination with other web3 elements, such as peer-to-peer video platforms (e.g., PeerTube or Odysee) or metaverse platforms, NFTs with extremist content can foster radicalization. Possible use cases for extremist NFTs are tokens of participation or loyalty, or the abuse of extremist memorabilia. Lastly, extremist NFTs open a potential new source of income for their minters when they are sold across the Internet.

Data Analysis Approach: NFT Collection & Classification

The analysis seeks to classify NFTs according to their ambiguity as propaganda material for the far-right. This includes NFTs that were not originally intended as far-right propaganda material but can be used as such. To get a rough estimate for the current extend of the dangers of NFT abuse, we first conducted a manual search for far-right extremism on NFTs. We searched existing NFT market places with far-right keywords, such as “1488”, “Holocaust” and “Hitler”. The marketplaces are intended to facilitate the trading of NFTs and usually provide a keyword-based search function that covers titles, descriptions and other metadata field of NFTs. The search prompted us with several results – most prominently a collection of NFTs by the Canadian white supremacist Stefan Molyneux, who is known to be an “early adopter” of web3 technologies in the field of far-right extremism. The initial results motivated a more systematic search for which we retrieved relevant NFT metadata from an API and classified the results into seven categories.

Figure 1: Screenshot of NFTs offered by white supremacist Stefan Molyneux on NFT market place OpenSea (as of Jan 27, 2023)

Data Collection & Processing

For this analysis, we conducted several data collection, data processing, and data exploration steps to generate the results presented in this report:

First, we accessed the NFT API of the web3 development platform “moralis”, which offers access to NFTs and their metadata across eleven blockchains in the Ethereum und Solana system. With a custom python-based search function for keywords, we collected results for keyword hits in the metadata of 7,500 NFTs. The results ranged across the chains listed in figure 2. The metadata elements varied from NFT to NFT but usually included a title, a general description and further details. We searched the API for matches on one of the following 83 English and German keywords:

Figure 2: Blockchain networks search via morialis API

'1488', '14words', '168:1', '20.4.', '2YT4U', '444', 'AdolfHitler', 'Anti-Antifa', 'Aryan', 'AryanBrotherhood', 'AtomwaffenDivision', 'BlackSun', 'Blood&Honour', 'C18', 'DefendEurope', 'Fasces', 'FeuerwaffenDivision', 'Goyim', 'Hakenkreuz', 'Hammerskins', 'Hitler', 'Hitlerjugend', 'HKNHRZ', 'HoGeSa', 'Holocaust', 'HooNaRa', 'IanStuart', 'IdentitarianLambda', 'IdentityEvropa', 'JeraRune', 'JewishOccupiedGovernment', 'JOG', 'KategorieC', 'Kekistan', 'KKK', 'Ku-Klux-Klan', 'Lambda', 'Landser', 'LeagueoftheSouth', 'Lunikoff', 'MeineEhreheißtTreue', 'NationalSocialistMovement', 'NewWorldOrder', 'NotEqual', 'NPD', 'NSM', 'NWO', 'Oidoxie', 'ProudBoys', 'Qanon', 'RAHOWA', 'Reconquista', 'RiseAboveMovement', 'RockAgainstCommunism', 'Rothschild', 'RudolfHess', 'Schutzstaffel', 'SiegHeil', 'Skinhead', 'Skrewdriver', 'Sleipnir', 'Sonnenrad', 'SS', 'SSBolts', 'Sturmabteilung', 'Swastika', 'TheHappyMerchant', 'ThorSteinar', 'Thule', 'Totenkopf', 'VanguardAmerica', 'Vinland', 'Volksfront', 'WhiteKnights', 'WhiteLivesMatter', 'WhitePower', 'Whiterex', 'WHTRX', 'WikingJugend', 'WWG1WGA', 'ZionistOccupiedGovernment', 'ZOG', 'ZyklonB'

The list was compiled manually by searching for far-right code and slang words in English and German, making extensive use of the Anti-Defamation Leagues’s Hate Symbols Database. This list is non-exhaustive and can be expanded for further data mining and analysis. The focus of the present analysis lied on retaining a list whose results could still be manually classified.

Second, we refined the results of the keyword search by an initial data assessment. The assessment sought to spot bunching of (irrelevant) results and remove mislead keywords. Keywords like “ZOG” (Zionist Occupied Government), “JOG” (Jewish Occupied Governemnt), “444” (numeric representation of “DdD” which stands for “Germany for Germans”), “1488” (numeric representation of “ADHH” which stand for “To Germany, Heil Hitler”) or “C18” (Combat-18) yielded an abundance of results in NFT metadata since the search mechanism would only look for the literal representation of the keywords and cannot contextualize them as far-right. Therefore, any representation of the “C18” or “1488” also as part of words, usernames, wallet IDs or hashes returned a result. By filtering though the keywords, we removed approx. 3,000 NFTs whose keywords were not specific enough. 4,445 NFTs remained in the dataset.

Third, to enable the classification of the retrieved NFTs into the seven categories, we had to download the actual NFT files from relevant HTTP or IPFS hosts. Especially requests for the Interplanetary File System (IPFS) were not always responsive. We tried to download every file three times and successfully retrieved 3,087 NFT files (approx. 70% of all NFTs after the pre-selection phase). Most files are in the form of images (JPG, PNG), a few as animations (GIF) and videos (MP4).

Fourth, we categorized the 4,445 NFTs (after pre-selection) into the seven categories described below. To decide upon the relevant category for each NFT, we assessed all available metadata and the downloaded NFT file (if given). Certain NFTs appeared as bulk NFTs, which means that they showed only minimal differences, such as their name, a few words in their description or the unique identifier, always in their metadata and partially in the NFT file. We assessed bulk NFTs individually for potential differences but classified them jointly to quicken the classification process. The relevant category for bulk NFTs can be decisive, especially when looking chains or keywords with limited results (see Chapter 5).

Fifth, as a last step to the analysis, we evaluated the results in each category, as well as regarding the relevant keywords and related blockchains. The evaluation was done both, visually and numerically. Relevant results are details hereafter. To facilitate the easy apprehension of data and results, we provided a preliminary report in an interactive “R/Shiny” application.

Categories to classify far-right extremist NFTs

To assess future NFT results, we set-up seven categories. The classification sought to analyze the levels of ambiguity towards their match with far-right topics and themes, as well as their ambiguity towards the use or potential abuse of these NFT as far-right propaganda material.

Category 1 “Extremist” includes NFTs that are clearly far-right extremist and were “likely made with far-right intention in mind”. NFTs in this category include, among others, Nazi glorification, anti-Semitism, anti-LGBTQ+, racism and (far-right) conspiracies. Category 1 is unambiguously extremist and unambiguously matching far-right topics and themes.

Category 2 “Far-Right Appeal” contains NFTs that are possibly but not clearly far-right extremist. The relevant difference to categories 1 and 3 is the potential for extremist abuse, while the origination might not have been intended to use the NFT for an extremist purpose. This category contains Nazi memorabilia, historical documents without context (e.g., pictures of the Holocaust), the “artistic” use of extremist symbols or automatically generated content. Category 2 is unambiguously matching far-right topics and themes and possibly extremist with a remaining level of ambiguity.

Category 3 “Connection to Far-Right Themes” comprises NFTs that reflect far-right topics but are clearly not extremist. The classification mostly stems from the combination of NFT image/video/animation with its metadata. The category contains historical documents with the relevant context, anti-war art or files clearly opposing far-right extremism. Category 3 is unambiguously non-extremist and unambiguously matching far-right topics and themes.

Category 4 “No connection” contains all NFTs that do not show any connection to far-right extremism and do not touch upon extremist themes either. While the content is largely random, all NFTs in this category are mismatches, often stemming from the dual use of the searched keywords. Category 4 is clearly not matching far-right topics and themes and clearly not extremist.

Category 5 “Unclear” comprises NFTs that could not be categorized into any other category. They sometimes show tendencies of towards far-right extremist topics and these but are not indicative. Some are simply not understandable or confusing. Category 5 is mostly not matching far-right topics and themes and possibly not extremist.

Category 6 “Mocking” all NFT which make fun of far-right topics and themes. The category also includes all antifa references, pro-Semitic and anti-right NFTs. Especially mocking depictions of Adolf Hitler are prominent examples of this category. The difference to category 4 lies in the use of humor and mockery for this category. Category 6 is, by definition, clearly matching far-right topics and themes and clearly not extremist.

Category 7 “No Data” contains all NFTs where not enough information is available. This means that either no metadata was readable and/or the file (image/video/animation) was inconclusive or not readable either. Category 7 is unclear about matching far-right topics and themes and unclear with regards to extremist content.

Figure 3: Examples of NFTs in Category 1 “Extremist”

Figure 4: Examples of NFTs in Category 2 “Far-Right Appeal”

Figure 5: Examples of NFTs in Category 4 "No Connection"

Figure 7: Examples of NFTs in Category 6 "Mocking"

Results: Far-Right Extremist Content is Rare but Present

Overall, we were able to extract 7,500 NFTs from 11 blockchains. As some keywords created too many random hits, we sub-selected relevant keywords based on the clarity of their results. After this pre-selection, 4,445 results remained. For 70% of these results, we successfully downloaded the NFT files as images, videos or animations. To assess the collected images and metadata on potentially extremist NFTs, we established seven categories to determine their ambiguity as far-right extremist propaganda material.

Comparison by Categories

he composition of the entire NFT data set across all chains shows that the majority of NFTs has no connection to far-right extremism despite the mentioning of relevant keywords. Roughly 2% of the available data is categorized as clearly extremist. A larger share of approx. 17% was categorized as “appealing to far-right topics”. This category consists of NFTs that could be used by extremists to share their ideology, even if the creator of the NFT did not intent such as purpose. This group contains a mentionable number of Nazi memorabilia as well as historical documents without context. The largest group contains those NFTs classified as Category 4 “No Connection”. Despite one (or more) of the 83 keywords in the metadata (e.g., title, description, details), the NFT did not have any connection to far-right topics. A reoccurring example of a mismatch were wine bottles: Keyword search for “Rothschild” yield hits on numerous depictions of “Chateau Rothschild” red wine from France, even though the keyword was geared towards far-right extremist narratives around the anti-Semitic Rothschild conspiracy. A little less than 5% of all NFTs are sorted as Category 6 “mocking”, meaning that they ridicule far-right topics. Here depictions of Adolf Hitler and other Nazi personnel are especially prevalent. Other categories, such as 'unclear' and 'no data' amount to approx. 6%.

Figure 8: Distribution of NFTs across categories

Figure 8: Table of categories, their levels of ambiguity and distribution of NFTs across categories

Comparison across Keywords

The analysis of the categorized results show strong differences in the overall number of found keywords (diagram on the right). More relevant keywords like 'Holocaust', 'Hitler' or 'Kekistan' yield much more results than niche keywords like 'TheHappyMerchant', 'WhiteLivesMatter', or 'Hakenkreuz'. The analysis of relative mentions show that certain keywords are still too broad (e.g., 'BlackSun'). Clearly extremist content can be found both at more prominent keywords and niche words. Overall, extremist content can be found in NFTs but it is comparatively scarce. The prominence of keywords is also relevant with regards to the category 'mocking': NFTs with prominent keywords ('Hitler', 'Aryan', 'QAnon') prompt an anti-fascist response. Lastly, NFTs with rather unknown keywords, especially far-right code words or far-right slang ('Goyim', 'WWG1WGA', 'Schutzstaffel'), yield much fewer but more clearly extremist results. The use of coded language also transcends into NFT minting.

Figure 9: Results and insights of NFT classification by keywords

Figure 10: Relative and Absolute Distribution of classified NFTs per Keyword (across all Chains)

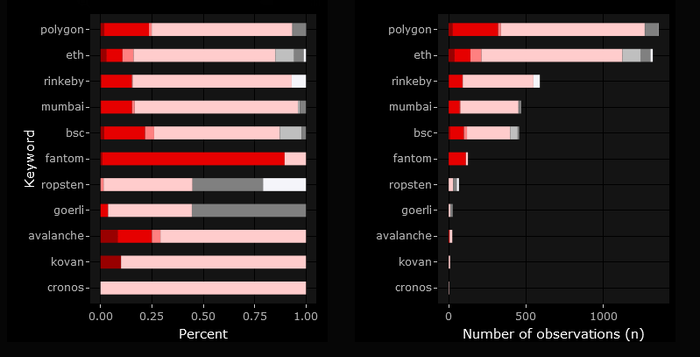

Comparison across Blockchains

Analyzing the results of all 4,445 NFTs across the different available blockchains from the moralis API, we see vast differences that follow an intuitive logic: Chains that are more prominent return more results; less prominent (or widely used) chains return fewer results. The blockchains Polygon Mainnet (“polygon”) and Ethereum Mainnet (“eth”) return well beyond 1,000 hits for our keyword search. Smaller chains like the Avalanche C-Chain Mainchain (“avalanche”) or the Ethereum Görli Testnet (“goerli”) return less than 50 results combined. Chains with more results show a rather stable return of extremist content between 1 to 5 %. Possibly extremist content was found in up to 25 % of the NFTs. The results for “smaller” chains vary drastically while putting especially the Fantom Mainnet in the spotlight. The question why Fantom yields a particularly high share of possibly extremist content requires further analysis.

Figure 11: Relative and Absolute Distribution of Categories per Chain (with all Keywords)

Findings & Outlook: Better Research to Leverage Web3 Analytics for Security Questions

To better understand the connection between NFTs and (far-right) extremist content, we collected 7.5k NFT and their metadata from 11 blockchains. Categorizing the NFT by their title, description, details and visual assessment of the downloaded images/GIFs/videos, we conclude that far-right extremist content is spread via NFTs on different blockchains. Looking at the metadata and images of pre-selected 4.5k NFT from a keyword search, only a small share of NFTs is clearly extremist (2%). Much more content with relevant keywords in NFT metadata could be used for extremist purposes but is not extremist per se (approx. 15 %).

We learned that more specific keywords, produce more relevant results, that extremist slang/code is propagated into NFT descriptions and yields more extremist results when searched for. But: Extremist code only produces clearer results as long as the keywords remain distinguishable and not context-dependent. Context-sensitive, extremist 'codes', such as number combinations, cannot be detected with a keyword-based search method. This produces an unknown share of undetected extremist NFTs. The classification process was done manually which is a time-consuming process that does not scale well with more data. Automatization or even AI-based approaches to support the manual work are challenging since the categorization as extremist remains contextual and usually requires a description-image-context combination.

Overall, the analysis remains a spot-check since it is not feasible to collect all NFTs across multiple chains; just like NFTs remain unseen if relevant keywords are unknown.

While this analysis has shown that NFT are not yet a major ground for extremists to play on, it became clear that there is a potential for its exploitation of the decentralized web. The uncertainty about the future and the relevance of Web3 as a mainstream technology prompt law enforcement, research and civil society with a well-known dilemma: While uncertainty impedes research funding as it increases the “option value of waiting”, hesitation likely leads to worse outcomes or late realization. Experiences in the field of extremism illustrate the importance of countering concerning developments as early as possible to prevent harmful content or behavior from spreading into society’s everyday life.

To address the dilemma and preempt the possible deterioration, we recommend to increase academic research on the exploitation of web3 in the field of national security studies and/or counter-terrorism. Current research is centered on the financial and technical elements of web3 development (in particular: decentralized finance) but little light is shed on questions of the societal impact of web3, especially with regards to security. In cooperation with private companies and civil society, it is important to dive deeper into the topic from an academic perspective and provide decision makers with a reliable data basis to ground their work in. With regards to the results presented here, we suggest to broaden the scope of the data collection: A larger number of diverse keywords, different languages and further chains will yield even more insightful results about the current status of extremism on NFTs.

Ultimately, web3 research should leverage the transparency of blockchains to quantify pending security questions, reduce the uncertainty of this technological development and anticipate future needs for law enforcement and intelligence agencies. To fight extremism in new technological fields, OSINT and cybercrime capabilities of law enforcement agencies will require drastic growth. And their adjacent competencies must be thought closer together: The future Internet requires a combination of open source intelligence and cybercrime-oriented data analytics that does not care whether the data comes from “classic” websites (web1), social media platform (web2) or blockchains (web3). This future of “Internet intelligence” (INTINT) seamlessly combines classical open source intelligence (OSINT) with social media intelligence (SOCMINT) and blockchain intelligence (BLOCKINT).

The high uncertainty around technological development, such as web3, burdens swift decision making and foresightful acting. Anticipatory analytics, as shown here with regards to extremism on NFTs, pave the way for going from the unknown unkowns to the known unknowns. And even if web3 technologies do not become core challenges for LEA in the second half of the 2020s, the call for more and better Internet intelligence is failsafe: Current demands for better Internet investigation already exceed current law enforcement capabilities by far – better skills and more staff therefore not only serve future challenges but also address very current problems in counter security threats on the Internet.