The U.S. Intelligence community describes its objective as “to provide timely, insightful, objective, and relevant intelligence about the activities, capabilities, plans, and intentions of foreign powers, organizations, persons, and their agents to inform decisions on national security issues and events” (U.S. Intelligence Community, 2020, p. 1). Violent non-state actors also delegate highly sensitive tasks to their intelligence organization(s): Plan attacks, protect themselves from counter-attacks as well as counter-intelligence and shape their overall operational environment (Tantalakis, 2019 after Gentry, 2016). The specific purposes of state and non-state intelligence create an institutional environment of formal and informal patterns that shape the structural setup of the respective organizations. Once running, these structures influence intelligence activities, which themselves reflect back and influence the organizational structures – the key dynamic of institutional development (Jacobides, 2007). Intelligence organizations on both sides are limited in their activities and structure by personnel, resources, laws, geographic access, knowledge, know-how and partially the public opinion.

Addressing interactions and limitations, this paper compares structural and activity-related differences between intelligence organizations of states and violent non-state actors (VNSA) and seeks to provide explanations and effects of the distinct setup. It is important to mention that the following findings assume typical structures and activities which may vary heavily in reality. In fact, there is little standardization of intelligence on either side: Non-state actors like militias, insurgent groups, terrorists, particular groups of organized crime or warlords (Williams, 2008) differ vastly by factors such as their ambition (succession, revolution, restoration, etc.), local conditions (geography, demographics, leadership, training etc.), strategy (Maoist, Castroite etc.) and organizational structure (political, military, tribal, cell, urban etc.) (Krause, 1996). Similarly, generalizations of state actor intelligence also fall short as the organizations differ by factors such as their budget, political and legal structure (democracy vs authoritarianism), compartmentalization or a state’s geopolitical threats and goals. Authoritarian regimes, for example, are more likely to have a politicized intelligence apparatus, with bad internal communication and information sharing (“turf wars”), a potential lack of competency as leaders are chose because of their loyalty, not ability, and higher corruption (Byman, 2017). The paper therefore requests the reader to cautiously question the generalization made in the following and expects a careful derivation from the general to the particular.

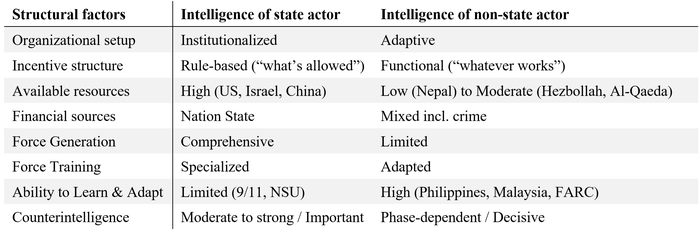

Structural Differences of State and Non-State Intelligence

Adapting factors for fighting wars to the intelligence setup (Gentry, 2015) and comparing intelligence organizations of state and non-state actor reveals profound structural differences:

Organizational Setup. State intelligence services are not single-purpose organizations that focus on one adversary or task only. Instead, they oversee a range of threat actors in their fields (e.g., counter-terrorism, counter-insurgency, counter-intelligence). Their longer existence and experiences lead to established “institutions” in the form of engrained pattern, organizational constellations and prescribed roles. As designed by the forethinkers of bureaucracy (e.g., Max Weber), the institutionalized organization does not depend on individual people and their unique skillset but requires a rationalization and compartmentalization of processes away from the human (Kieser, 2006). This segmented setup of state intelligence creates a series of well-studied coordination problems: Prominent examples are cooperation failures between units that undermined successful warning and prevention of the September 11 attacks in the US (Best, 2015) or the far-right insurgency of the German “National Socialist Underground” between 1998 and 2011 (Von Der Behrens, 2018). In an extreme form, compartmentalization leads to “stove piping” as seen during the Northern Ireland conflict (approx. 1970-1995). Here, the British managed organizatially-segregated types of intelligence (security and political intelligence) so separately that they appeared independent and lacked mutual reinforcement (Craig, 2018).

Unlike state intelligence, violent non-state actors typically appear with a distinct goal – as a single-purpose organization (e.g., coup d’état, political influence, financial gains etc.). With their emergence, the VNSA intelligence is usually built from scratch. The little institutionalization leads to a more human-focused and less organization-dependent setup that allows for more flexibility, quicker adaption and less slack but suffers from a higher vulnerability against targeted disruption. The level of institutionalization depends highly on the current phase of the VSNA (Krause, 1996): If the non-state actor is still in the organizational or guerilla phase, capabilities (and challenges) are not as extensive as in the conventional warfare phase where the VSNA requires a sufficiently mature organizational structure and intelligence capabilities to withstand its usually superior state adversary. The less engrained setup of VNSA intelligence allows for a quicker interaction between structures and activities, particularly from activities to structure, as in younger organizations the setup functionally follows its tasks and not vice versa.

Incentive Structures. The institutionalization of state and non-state intelligence is echoed in the staffs’ incentive structure: Where state intelligence is required to comply with organizational or legal rules and can do “what’s allowed”, VNSA intelligence is usually less regulated by rules as laws are ignored and organizational procedure are just emerging. Their approach is more functional, allowing them to do “whatever works”. Despite lacking comparative research on the topic, it can be speculated that the organizational setting and incentive structure shape the individual motivation: While state intelligence officers are rotating in positions and participate in several intelligence tasks, their intrinsic motivation is believed to be lower. Non-state intelligence, on the other side, is expected to incorporate more purpose-driven staff that decides to join a VNSA for its one dedicated goal (insurgency, terrorism, crime etc.).

Available Resources. State intelligence benefits from generally higher and more readily available resources than non-state intelligence. “Key resources included money, types of committed organizations, and human skills, especially the cultural expertise and language skills especially useful for HUMINT collection and analysis.” (Gentry, 2010, p. 68) The lack of sufficient resources severely limits a non-state actor as seen in the case of smaller insurgency groups like the Maoist insurgents in Nepal (Jackson, 2019). The inflow of resources for state intelligence is exclusively limited to the backing nation state – as non-state funding would resolve in non-state influence on sensitive areas of a government. The financial sources for VNSA can stem from various sources such as private founding (PIRA in Northern Ireland see Maguire, 1990), extorsion of controlled areas (Islamic State in the Middle East, see Wege, 2018), criminal economic activity (Cali cartel in Colombia, see Mobley & Ray, 2019), the Taliban in Afghanistan (Staniland, 2012), legal business (FARC in Colombia, see Gentry & Spencer, 2010) or even competing state intelligence agencies (via paying informants, e.g., NSU terrorism in Germany, see Koehler, 2016).

Force Generation & Training. Force generation of state intelligence usually draws from a more comprehensive range of candidates with specific recruitment units, strategies and pools, such as regular military organizations, police units or specialized universities. VNSA intelligence, on the other side, is limited to the local network of members and recruitment from the territory they are active in. Volunteering recruits are a potential counter-intelligence threat to both sides but particularly the VNSA that depends more on this form of passive force generation. Due to the larger organizations, officers from state intelligence usually receive a more specialized training after recruitment. If available at all, VNSA members receive less training and specialization and are required to learn and adapt “on the job”.

Learning & Adaptation. As seen with training new forces as well as the rapid organizational development of VNSA intelligence, Gentry underlines that “[a]ccurate learning and effective adaptation were essential to success. Counterinsurgent states that learned and adapted better, even if not faster, than their adversaries won; prominently successful cases of adaptation include the Philippines and Malaya cases.” (Gentry, 2010, p. 68) Despite the unanimous scholarly opinion that learning and adaption is equally important for state intelligence, its organizations are considered “bad learners and adapters” – frequently referencing the attacks of September 11 (Zegart, 2009). Acknowledging that boiling down the complex setting that lead to the 9/11 intelligence failure to one factor is insufficient (Gentry, 2010), the compartmentalized organizational setting, as well as the more rule-based incentive structure of state actor intelligence conceptually impede a quick reaction to new developments. This inability to quickly learn and adapt is particularly problematic when fighting a violent non-state actor that exploits its competitive advantage of new threats, tactics and techniques.

Counter-Intelligence. While effective counter-intelligence (CI) can stall or harm a state actor, it usually does not threaten the actor’s existence. For VNSA, the existence and effectiveness of counter-intelligence is a question of life or death: Once attacked by a state intelligence agency, the VNSA can only sustain if the integrity of the insurgency, terror group or syndicate remains intact. Many insurgent groups suffer from particularly poor CI despite a desperate need for it; for example, the Colombian FARC rebels whose faulty counter-intelligence was only met by the equally poor Colombian state intelligence which otherwise could have ended the conflict much earlier (Gentry & Spencer, 2010). Others have mastered CI and successfully defended intrusion like Al Qaeda that established a sophisticated recruitment, communication and cell structure as well as extensive operation security measures that made a penetration by foreign actors particularly difficult. In return, the group had repeatedly placed and accessed cover agents or informants in FiveEyes intelligence agencies like the FBI (Ilardi, 2009). As seen in the famous example of the Northern Irish “Steak Knife” double agent (Bamford, 2005), the quality of a VNSA counter-intelligence is a tipping point for insurgents, terrorists and criminals. Protecting this single point of failure must be of utmost importance.

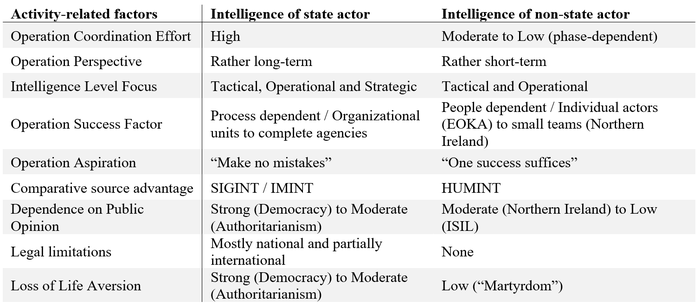

Activity-Related Differences of State and Non-State Intelligence

In addition to the structural differences, there are several factors that shape activities of state and non-state intelligence:

Operations. Due to the more rigid structures, state intelligence has a higher coordination effort for operations, making activities more costly and/or time-consuming. The coordination effect concurs with the long-term operational perspective of state intelligence that ideally focuses on winning the war, not the battle, and generates products on all three intelligence levels: tactical, operational and strategic. Long-term operations with a multitude of missions and activities need to account for the abovementioned structural factors, such as the rotation of intelligence officers, learning and adaption to new methods of the adversary or shifting resources. The operation aspiration and the long-term perspective of a state actor intelligence organization can be summarized as “mistake aversive” when focusing on preventing a non-state actor from striking to avoid the loss of life, media attention for the adversary or public humiliation. In general, the success of individual activities, long-term operations and “making no mistake” at state intelligence is organization and less people-dependent.

Intelligence organizations of violent non-state actors, on the contrary, benefit from a more flexible organizational structure and require less coordination effort. The more flexible backchannel from activities to structure facilitates “creative approaches” as seen with the Colombian FARC insurgency that set up computer repair shops in the proximity of facilities of the Colombian military and extracted information from devices that the shops were requested to repair (Gentry & Spencer, 2010). Activities of VNSA follow a more try-and-error approach under the motto “one success suffices” as many failures will be outweigh by one success (for example, 83 % prevented Jihadi terrorist attacks in the US from 1993-2016 versus the impact of Al Qaeda’s September 11 attacks, see Crenshaw, Dahl, & Wilson, 2017). Due to the limited resources and lower experience, VNSA organizations focus mostly on the tactical and partially the operational level as strategic intelligence is mostly not available or neglected for lacking immediate concern (Gentry & Spencer, 2010). Overall, activities of VNSA intelligence heavily rely on the qualities of the individuals involved. A prime example of this people-dependence is the charismatic leader of the Greek Cypriot nationalist guerrilla organization EOKA, Georgios Grivas, who established a sophisticated intelligence network for his insurgency on the island (Slack, 2019).

Intelligence Sources. Comparing intelligence sources between state and non-state actors, both have a comparative advantage over the other: State intelligence agencies are typically able to access tech and resource-savvy sources, like signals and sensor (SIGINT), pictures (IMINT), geo-spatial data (GEOINT), in addition to standard sources like HUMINT or OSINT, and apply advanced analytical methods and computation power for their analysis. This comparative advantage not only increases the information base of state intelligence but indirectly disrupts the VNSA’s structure as they are uncertain about when they are surveilled and when not. VNSA intelligence, on the contrary, typically focuses on low-threshold information: Sophisticated informant networks and a strong HUMINT inflow of a local support base can develop into comparative advantage over the state adversary in an area. Prominent examples are the Maoist insurgency in Nepal (Jackson, 2019), that – despite little resources – ran an extensive informant network and penetrated its adversary successfully, and the aforementioned Cypriote insurgency against the British in the 1950s that benefitted from very close ties and excellent HUMINT from the local population (Slack, 2019). A third example shows the interplay of comparative advantages between state and non-state actors: The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) benefited from the broad availability of HUMINT via its draconic rule over controlled territories but was not able to defend hostile SIGINT extraction or to collect its own tech-savvy intelligence (Wege, 2018).

Legal and reputational limitations. A third set of activity-related differences between state and non-state intelligence focusses on the legal and reputational limitations of operations. State intelligence, in particular in liberal democracies, are closely tied to a legal framework with typically specific legislation on the conduct of intelligence organizations. The compliance with national and international law varies with legal specificity on intelligence and the predominance of the rule of law in state actors but generally stalls operations, limits creativity and creates a comparative disadvantage to VNSA that disrespect the law.

Reputational limitations apply to state and non-state actors more evenly but can still differ greatly between individual actors. In particular countries with free press have to take the public perception of their intelligence action into account as decision makers are influenced by, for example, potential repercussions in elections or at court. French intelligence operations in Algeria exemplify the mis-assessment of reputational limitations when using torture to generate intelligence on the counterinsurgent Front de Libération Nationale (FLN). Wide-spread knowledge and disapproval of these intelligence methods undermined the French stance in Algeria and contributed to the overall loss of the colony (Francois, 2008; Gentry, 2010). In addition to the reputational limitation, state actors are typically more averse to the loss of life – be it operating staff or civilian casualties. VNSA can actively exploit a state actors’ reputation vulnerability and the loss of life aversion in a mixture of deception and information campaign. In fact, the element of fear is at the heart of terrorist media campaigns (Gentry, 2015). Insurgency groups are partially dependent on the public opinion as it influences their local support, resource inflow and recruitment. Dependent groups tend to apply a wide range of propaganda to construct a legitimate claim for possibly disapproved activities as prominently seen in the case of the PIRA in Northern Ireland (Bamford, 2005). The relevance of the reputational limitation can also be seen in this last example of the British support in Dhofar, Oman. Unlike in Northern Ireland, the limited public attention to the problem allowed for effective counter-measures against an “insurgency out of the sight and mind of a global audience” (Jones, 2014).

Conclusion: Differences matter.

Comparing structural and activity-related factors, state and non-state intelligence organizations show parallels to large-scale corporation and young start-ups. Like grown companies, the organizational setup renders state intelligence more resilient but less effective, whereas VNSA intelligence is less resilient but more effective as are start-ups. While the non-state actor’s survival depends on sufficient (counter-)intelligence, state intelligence focusses more on the protection of life, as well as legal and reputational factors. Both sides – start-up versus corporation and state actor intelligence versus VNSA intelligence – remain a key issue of scrutiny for a better understanding and development of the respective organizations.

This paper was submitted as final paper to the course "Intelligence & War" at Columbia

University's School of International and Public Administration (SIPA), lectured by Prof John A. Gentry, former CIA and DIA officer and now Adjunct Associate Professor at SIPA.

LITERATURE

- Bamford, Bradley W.C. “The Role and Effectiveness of Intelligence in Northern Ireland.” Intelligence and National Security 20, no. 4 (2005): 581–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684520500425273.

- Behrens, Antonia Von Der. “Lessons from Germany’s NSU Case.” Race and Class 59, no. 4 (2018): 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396817751307.

- Best, Richard A. “Intelligence and U.S. National Security Policy.” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 28, no. 3 (2015): 449–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2015.1022460.

- Byman, Daniel. “US Counterterrorism Intelligence Cooperation with the Developing World and Its Limits.” Intelligence and National Security 32, no. 2 (2017): 145–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2016.1235379.

- Craig, Tony. “‘You Will Be Responsible to the GOC’. Stovepiping and the Problem of Divergent Intelligence Gathering Networks in Northern Ireland, 1969–1975.” Intelligence and National Security 33, no. 2 (2018): 211–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2017.1349036.

- Crenshaw, Martha, Erik J. Dahl, and Margaret Wilson. “START Research Brief: Jihadist Terrorist Plots in the United States.” Comparing Failed, Foiled, Completed and Successful Terrorist Attacks, 2017.

- Francois, Philippe. “Waging Counterinsurgency in Algeria: A French Point of View.” Military Review, no. October (2008): 56–67.

- Gentry, John A. “Intelligence Learning and Adaptation: Lessons from Counterinsurgency Wars.” Intelligence and National Security 25, no. 1 (2010): 50–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684521003588112.

- ———. “Toward a Theory of Non-State Actors’ Intelligence.” Intelligence and National Security 31, no. 4 (June 6, 2016): 465–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2015.1062320.

- ———. “Warning Analysis: Focusing on Perceptions of Vulnerability.” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 28, no. 1 (2015): 64–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2014.962354.

- Gentry, John A., and David E. Spencer. “Colombia’s FARC: A Portrait of Insurgent Intelligence.” Intelligence and National Security 25, no. 4 (2010): 453–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2010.537024.

- Ilardi, Gaetano Joe. “Al-Qaeda’s Counterintelligence Doctrine: The Pursuit of Operational Certainty and Control.” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 22, no. 2 (2009): 246–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/08850600802698226.

- Jackson, Paul. “Intelligence in a Modern Insurgency: The Case of the Maoist Insurgency in Nepal.” Intelligence and National Security 34, no. 7 (2019): 999–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2019.1589677.

- Jacobides, Michael G. “The Inherent Limits of Organizational Structure and the Unfulfilled Role of Hierarchy: Lessons from a Near-War.” Organization Science 18, no. 3 (June 2007): 455–77. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0278.

- Jones, Clive. “Military Intelligence and the War in Dhofar: An Appraisal.” Small Wars and Insurgencies 25, no. 3 (2014): 628–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2014.913743.

- Kieser, Anton. “Max Webers Analyse Der Bürokratie.” In Organizationstheorien, edited by Hans Ebers and Anton Kieser. Stuttgart, 2006.

- Koehler, Daniel. Right-Wing Terrorism in the 21st Century: The ‘National Socialist Underground’ and the History of Terror from the Far-Right in Germany. 1st editio. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Krause, Lincoln B. “Insurgent Intelligence: The Guerrilla Grapevine.” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 9, no. 3 (1996): 291–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/08850609608435319.

- Maguire, Keith. “The Intelligence War in Northern Ireland.” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 4, no. 2 (1990): 145–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/08850609008435136.

- Mobley, Blake W., and Timothy Ray. “The Cali Cartel and Counterintelligence.” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 32, no. 1 (2019): 30–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2018.1522218.

- Slack, Keith C. “EOKA Intelligence and Counterintelligence.” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 32, no. 1 (2019): 82–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2018.1522228.

- Staniland, Paul. “Organizing Insurgency: Networks, Resources, and Rebellion in South Asia.” International Security 37, no. 1 (July 2012): 142–77. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00091.

- Tantalakis, Evripidis. “Insurgents’ Intelligence Network and Practices during the Greek Civil War.” Intelligence and National Security 34, no. 7 (2019): 1045–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2019.1668718.

- U.S. Intelligence Community. “Our Values - Objectivity.” Intel.gov, 2020. https://www.intelligence.gov/index.php/mission/our-values/342-objectivity.

- Wege, Carl Anthony. “The Changing Islamic State Intelligence Apparatus.” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 31, no. 2 (2018): 271–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2018.1418552.

- Williams, Phil. “Violent Non-State Actors and National and International Security.” Zürich, 2008. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/93880/vnsas.pdf.

- Zegart, B. Amy. Spying Blind: The CIA, the FBI, and the Origins of 9/11. 1st editio. Princeton University Press, 2009.

Write a comment